Farmers, like other business owners, may deduct “ordinary and necessary expenses paid . . . in carrying on any trade or business.” IRC § 162. In agriculture, these ordinary and necessary expenses include car and truck expenses, fertilizer, seed, rent, insurance, fuel, and other costs of operating a farm. Schedule F itemizes many of these expenses in Part II. Those properly deductible expenses not separately listed on the Form are reported on line 32. Following is a summary of several key expense deductions for farmers.

Farmers, like other business owners, have the option to either (1) deduct the actual cost of operating a truck or car in their business or (2) deduct the standard mileage rate for each mile of business use.

Those taxpayers who choose the actual cost method may deduct those expenses related to the business use of the vehicle. These include gasoline, oil, repairs, license tags, insurance, and depreciation (subject to certain limits). Farmers choosing this method must keep good records of these expenses. (See Depreciation section below for rules for depreciating various vehicles used in the farm business).

The standard mileage rate for 2019 is 58 cents per mile (57.5 cents in 2020). Taxpayers that operate five or more cars or light trucks at the same time are not eligible to use the standard mileage rate. Nor can the standard mileage rate be used if the owner has taken an IRC § 179 or other depreciation deduction for the vehicle.

When vehicles are used for both personal and business purposes, the taxpayer may take deductions only for the percentage of use attributable to the business. This requires detailed recordkeeping. Farmers, however, have a special rule under which they can claim 75% of the use of a car or light truck as business use without any allocation records. Treas. Reg. § 1.274-6T(b). The rule applies if the taxpayer used the vehicle during most of the normal business day directly in connection with the business of farming. A farmer chooses this method of substantiating business use the first year the vehicle is placed in service. Once that choice is made, it cannot be changed.

A farmer who uses his vehicle more than 75% for business purposes should keep records of business use vs. personal use. He may then deduct the actual percentage of expenses applicable to the business use.

Active farmers may be able to presently deduct the cost of conservation practices implemented as part of an NRCS-approved (or comparable state-approved) plan. Farmers can elect the IRC § 175 soil and water conservation deduction (which is taken in the year the improvements are made) for conservation expenditures in an amount up to 25 percent of the farmer’s gross income from farming. The deduction can only be taken for improvements made on “land used for farming.” Excess amounts may be carried forward to future tax years. Once the farmer makes this expense election, it is the only method available to claim soil and conservation expenses. If the farmer stops farming or dies before the full cost has been deducted, any unused deduction is lost. It cannot then be capitalized to reduce any gain upon the sale of the farm. Landowners who are not eligible for the deduction must capitalize the expenses (add them to the basis of the property).

The IRC § 175 deduction is only available to taxpayers “engaged in the business of farming.” IRC § 175(a). A taxpayer is engaged in the business of farming if he “cultivates, operates, or manages a farm for gain or profit, either as owner or tenant.” Treas. Reg. § § 1.175–3. A taxpayer who receives a rental (either in cash or in kind) which is based upon farm production is engaged in the business of farming for purposes of the conservation deduction. However, a taxpayer who receives a fixed rental (without reference to production) is engaged in the business of farming only if he participates to a material extent in the operation or management of the farm. A taxpayer engaged in forestry or the growing of timber is not engaged in the business of farming; nor is a person cultivating or operating a farm for recreation or pleasure rather than a profit.

IRC § 175 allows eligible taxpayers to deduct certain expenses for:

Specifically, these expenses can include.

See IRS Publication 225, Conservation Expenses

Karl farmed his ground for 20 years before cash renting it to his neighbor. Karl no longer participates in the farming activities on his land. In 2020, Karl spent $20,000 on an NRCS-approved terracing and grading project. He wants to deduct these expenses on his 2020 return.

Note that the IRC § 175 deduction is also not available for the purchase of depreciable assets (those that have a useful life). Furthermore, the cost of seed and other “ordinary and necessary” business expenses would be deductible in the year expended as ordinary business expenses, apart from IRC § 175. Cost sharing or incentive payments received to implement these conservation programs would then be taxed as ordinary income.

If a landowner who has taken a soil or water conservation deduction sells his property after holding it for five years or less, he or she will have to pay ordinary income taxes on the gain from the sale, up to the amount of the past deduction. If the property was held for less than 10 years, but more than five, that ordinary income rate is assessed against only a percentage of the prior deduction amount.

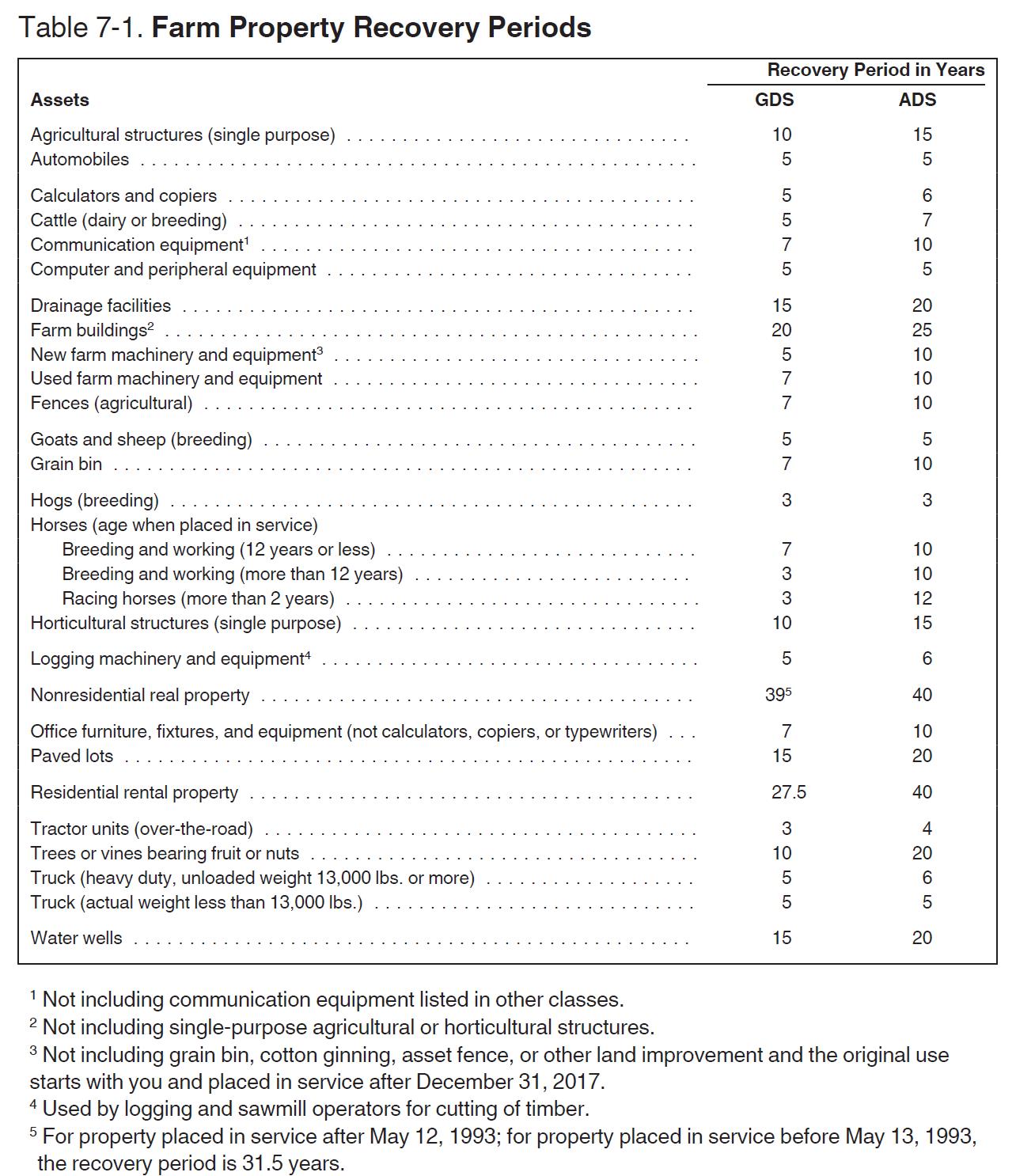

Farmers are allowed to depreciate assets over a period of years, based upon a recovery period for each type of asset. The Modified Accelerated Cost Recovery System (MACRS) is used to recover the basis of most business and investment property placed in service after 1986. MACRS consists of the General Depreciation System (GDS) and the Alternative Depreciation System (ADS). Farming taxpayers use GDS unless they are required to use ADS, most typically because they’ve opted out of the uniform capitalization rules. Beginning in 2018, farming and ranching property, if within the 3-, 5-, 7-, and 10-year recovery periods, is generally depreciated using the 200 percent declining balance method with half-year convention. Farmers may elect, however, to depreciate this property using the 150 percent declining balance method. Property in the 15- and 20-year recovery periods continue to use 150 percent declining balance method with half-year convention.

The following chart, reprinted from the 2019 IRS Publication 225, details recovery periods for standard farming assets.

The PATH Act permanently extended an enhanced “section 179” deduction for 2015 and beyond. The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) further enhanced this deduction. For 2019, farmers and small businesses could deduct up to $1,020.000 of the tax basis of certain business property or equipment placed into service that year. Once qualifying purchases reached a threshold of $2,550,000 in 2019, the amount of the deduction was reduced, dollar-for-dollar for each dollar above the threshold. The section 179 deduction, as well as the threshold, are indexed for inflation. For 2020, the amounts are $1,040,000 of tax basis and $2,590,000 for the investment threshold limit.

The section 179 deduction applies to both new and used business equipment. Because it applies to 15-year property or less, it does not apply to farm buildings, but can be used for single purpose agricultural structures, such as a hog barn.

In addition to setting a higher deduction amount, the PATH Act also made permanent a provision allowing revocation of the Section 179 election on an amended return without IRS consent. Once the election is revoked, it cannot again be elected again for the same tax year.

The TJCA increased additional first-year depreciation, also called bonus depreciation, by increasing the allowable amount to 100%, with a phase-down to sunset in 2026. Under this provision, producers can claim an additional first-year tax deduction equal to 100 percent of the value of qualifying property placed into service after September 27, 2017 through December 31, 2022. Congress then reduced the depreciation amount to 80 percent in 2023, 60 percent in 2024, 40 percent in 2025, and 20 percent in 2026. Bonus depreciation is slated to disappear altogether for property placed into service in 2027 or later, except for certain longer production property and aircraft which have an additional year of bonus depreciation available until December 31, 2027.

The bonus depreciation deduction, which is available for new and used property (under TCJA) property, applies to farm buildings, in addition to equipment. Unlike the §179 expense allowance, there is no limit on the overall amount of bonus depreciation that a producer may claim. If an item of property qualifies for both §179 expensing and bonus depreciation, the §179 expensing amount is computed first, and then bonus depreciation is taken based on the item’s remaining income tax basis. It is also important to note that §179 expensing is based on when the taxpayer’s tax year begins, whereas bonus depreciation is tied to the calendar year.

It is helpful to realize that expensing under §179 is an “election in” and the presumption of tax law is that the farmer/rancher uses bonus depreciation, thus it is an “election out” of using bonus depreciation. The election not to use bonus depreciation is made on a class by class basis and affects all assets purchased within the class, Farmers cannot modiry their bonus depreciation choices on an amended return.

IRC §280F(a) imposes dollar limitations on the depreciation deductions that can be taken on passenger vehicles. Passenger vehicles, by definition, weigh 6,000 lbs. gross vehicle weight or less. IRS Rev. Proc. 2019-26 set the 2019 limits as follows.

Depreciation limits for light-duty trucks and vans placed in service in 2019 for which bonus depreciation is taken are as follows:

Depreciation limits for light-duty trucks and vans placed in service in 2019 for which bonus depreciation is not taken are as follows:

Depreciation limits for passenger cars placed in service in 2019 for which bonus depreciation is taken are as follows:

Depreciation limits for passenger cars placed in service in 2019 for which bonus depreciation is not taken are as follows:

SUVs with a gross vehicle weight rating above 6,000 lbs. are not subject to depreciation limits. They are, however, limited to a $25,500 IRC §179 deduction for 2019 (25,900 in 2020). No depreciation or §179 limits apply to SUVs with a GVW more than 14,000 lbs. Trucks and vans with a GVW rating above 6,000 lbs., but not more than 14,000 lbs., generally have the same limits: no depreciation limitation, but a $25,500 IRC §179 deduction. These vehicles, however, are not subject to the §179 $25,500 limit if any of the following exceptions apply:

Libby purchased an SUV in February of 2019 for $45,000 as her primary farming vehicle. She is able to document 100 percent business use through travel logs. The SUV has a GVW of 8,000 lbs.

Libby can expense the SUV as follows:

$45,000

– $25,500 (Section 179)

= $19,500

-$19,500 (Bonus Depreciation)

$0

0 MACRS Depreciation (five-year, 150% DB)

=$0

Libby can deduct all of the $45,000 purchase in the first year using both section 179 and bonus. Alternatively, Libby can use 100% bonus to accomplish the same outcome for 2019.

Instead of purchasing an SUV, Libby purchased a long-bed pickup truck with a GVW more than 6,000 lbs. Now, Libby is subject to no §179 deduction, and can immediately expense the entire purchase (assuming she has not used the $1,020,000 §179 deduction for other purchases).

Libby decides to purchase a light-duty pickup truck instead. In this case, her entire deduction first year deduction will be limited to $18,100 in 2019.

Now suppose Libby purchases a used light-duty pickup truck. Because bonus depreciation applies to used purchases too, Libby’s 2019 first year deductions are limited to $18,100 if used 100% for business.

Under IRC § 180, taxpayers engaged in the business of farming may elect to immediately expense the cost of fertilizer and lime (where the benefits last substantially more than one year), rather than to capitalize the expense and depreciate it over the term of its useful life. The election is for one year only, but once such an election is made (by reporting the fertilizer and lime deduction on Schedule F, Line 17), it may not be revoked without the consent of the IRS. This provision applies both to tenants and landlords if the rent is based upon production. Cash rent landlords who do not materially participate in the farming operation may not take advantage of this tax benefit. It is also important to note that this deduction applies only to “land used in farming,” which is defined as land used “by the taxpayer or his tenant for the production of crops, fruits, or other agricultural products or for the sustenance of livestock.” Initial land preparation costs cannot be deducted.

Note that the amount of the fertilizer and lime deduction may be limited by the rule that restricts deductions for prepaid farm supplies to 50 percent of all other deductible farm expenses for the year. See Prepaid Supplies below.

If the farmer later sells the farmland for which the cost of the fertilizer or lime has been deducted, he or she must report the amount of the sales price attributable to the unused fertilizer or lime as ordinary income.

Interest paid on farm mortgages and other farming-related loans is deductible on Line 21 of Schedule F as an ordinary and necessary business expense. For cash method and accrual method farmers, interest is deductible in the year it is paid or accrued respectively. IRC §461(g)(1).

Cash land rent paid by a tenant is generally deductible on line 24b of Schedule F in the year it is paid. See note in Prepaying Expenses section below regarding prepaying rental expenses. Crop share rent is not deductible. Equipment rental payments made by a farmer are deductible on line 24a of Schedule F.

Farmers may generally deduct the cost of materials and supplies in the year in which they are purchased. Treas. Reg. § 1.162-3; Treas. Reg. § § 1.162-12. This would include deducting the cost of fuel, tools, and feed. Farmers may also generally deduct most expenses incurred for the repair and maintenance of their farm property. This would include deducting expenses for activities such as repairing the roof of a farm building or painting a fence. Expenditures that substantially prolong the life of property (restore), increase its value (betterment), or adapt it to a different use, however, must generally be capitalized, not deducted. Distinguishing capital expenditures from supplies, repairs, maintenance, and other deductible business expenses is sometimes a difficult process.

IRS issued the Tangible Property Regulations (T.D. 9636), effective January 1, 2014, to distinguish capital expenditures from supplies, repairs, maintenance, and other deductible business expenses. Treas. Reg.§ 1.263(a)-1 also provides taxpayers with an option to elect to apply a de minimis safe harbor to amounts paid to acquire or produce tangible property. If this election is made, the taxpayer need not determine whether every small dollar expenditure for the acquisition of property is properly deductible or capitalized under the complex acquisition and improvement rules of the regulations. Instead, the taxpayer must deduct every purchase up to the amount of the safe harbor elected.

For taxpayers without an applicable financial statement, the safe harbor amount for tax years beginning in and after 2017 is $2,500. If the taxpayer has an accounting procedure in place to expense such amounts, he or she can make the annual election. This election is not an accounting method change, but is made by attaching a statement to a timely filed original return. Once made for a particular tax year, every purchase of tangible property falling within the range of the election must be expensed. A taxpayer cannot choose to apply the safe harbor to some items and not to others.

When a taxpayer elects the de minimis safe harbor, the amount paid is not treated as a capital expenditure, as a repair, or as materials and supplies. Instead, the taxpayer deducts the amount of the purchase under Treas. Reg. §1.162-1, provided that the expense otherwise constitutes an “ordinary and necessary” business expense. If the items to be deducted don’t fit into an expense category included on Schedule F, they can be listed on line 32 as “other expenses.”

Generally, a taxpayer may not file an amended return to either make or revoke the election for the de minimis safe harbor. It is important to note that if a taxpayer later sells property expensed under the safe harbor at a gain, the taxpayer must pay ordinary income tax on the entire sale price. This is not considered IRC § 1221 or § 1231property. These sales would be reported on Form 4797 (Part II) (Sales of Business Property). If the property was not held for sale in the ordinary course or inventory, the gain should not be subject to self-employment tax.

Farmers may generally deduct the cost of seeds and plants used to produce a crop for sale. This deduction is taken on line 26 of Schedule F. This rule does not apply to plants with a pre-productive period of more than two years (i.e. trees and vines). Costs for these types of plants must generally be capitalized, not deducted as an ordinary business expense. Under the TCJA, farmers with gross incomes of $26,000,000 or less in 2019 are not subject to the UNICAP rules under IRC §263A and may generally deduct new plantings. See IRS Rev. Proc. 2020-13 for details regarding a farmer wanting to use the new exemption in the same year an election is in place through which a farmer elected out of UNICAP rules.

A farmer can generally deduct the following types of taxes on line 29 of Schedule F:

Note that state or local sales taxes imposed on the purchase of capital assets for use in farming operations must be capitalized, not deducted.

Cash-method taxpayers generally can deduct their expenses for the year in which they pay them. IRC § 461(a); Treas. Reg. § 1.461-1(a)(1). Some limits to deductions, however, occur with respect to the prepayment of expenses.

Cash basis farmers are generally allowed to prepay the cost of farm supplies such as feed, seed, and fertilizer by purchasing them in one year, even though they will not use the supplies until the following year. This allows farmers to shift deductions to an earlier tax year. The amount of the allowable deduction for prepaid expenses is limited by IRC § 464. Under this provision, the prepaid farm expenses may not exceed 50% of other deductible farm expenses (including depreciation), unless one of the following exceptions is met:

To qualify for an exception, the taxpayer must also be “farm-related,” meaning that one of the following must apply:

Note: In Agro-Jal Farming Enterprises, Inc. et al. v. Comm., 145 T.C. No. 5 (2015), the Tax Court stated that the 50% limitation applies narrowly to “feed, seed, fertilizer, or other similar farm supplies.” In other words, prepayments for farm supplies falling outside of that category (in the case of Agro-Jal, packing materials) may not be subject to that limitation.

If the prepaid farm supply expenses exceed 50 percent of all other expenses (and an exception does not apply), the amount of the expense deduction in excess of 50 percent must be deduced in the later tax year. In other words, the excess must be deducted when the supplies are actually used or consumed.

Note: “Farm syndicates” are not allowed to deduct seed, feed, fertilizer or other similar farm supplies until actually used or consumed. IRC § 464(c)(1) defines “farm syndicate” as:

(A) a partnership or any other enterprise other than a corporation which is not an S corporation engaged in the trade or business of farming, if at any time interests in such partnership or enterprise have been offered for sale in any offering required to be registered with any Federal or State agency having authority to regulate the offering of securities for sale, or

(B) a partnership or any other enterprise other than a corporation which is not an S corporation engaged in the trade or business of farming, if more than 35 percent of the losses during any period are allocable to limited partners or limited entrepreneurs.

The term “farming” for purposes of IRC § 464 means “the cultivation of land or the raising or harvesting of any agricultural or horticultural commodity including the raising, shearing, feeding, caring for, training, and management of animals.” Farming does not include timber for this purpose.

Note: IRC §461(g)(1) requires that cash method farmers deduct interest only in the year accrued and paid.

In addition to the above limitation, the cost of supplies bought in the current year for use in the following year is deductible by a cash basis taxpayer in the current year only if: (1) the expenditure is a payment for the purchase rather than a mere deposit ((2) the prepayment is made for a business purpose and not merely for tax avoidance; and (3) the deduction in the taxable year of prepayment does not result in a material distortion of income. Rev. Rul. 79-229; Heinold v. Commissioner, TC Memo 1979-496.

The material distortion of income test should met if the taxpayer meets the conditions of Treas. Reg. § 1.263(a)-4(f), issued in 2004. Under this regulation, a cash basis taxpayer may deduct (rather than capitalize) expenses where the benefits do not extend beyond the earlier of:

Although Rev. Rul. 79-229 specifically discussed prepaid livestock feed expenses, IRS applies these requirements to prepayments for all farm supply expenses. See, e.g. Farmer’s Audit Technique Guide, Chapter 4, Expenses, 2006.

Ryan, a cash method farmer, has paid $24,000 in deductible farm expenses at the end of 2020. He wants to prepay some seed and chemical expenses to deduct against some extra income he received this year. What is the maximum amount of expenses he can prepay for 2021 and deduct in 2020? What happens if he prepays $20,000?

Answer: As long as other requirements are met, Ryan may deduct $12,000 in qualifying, prepaid expenses in 2020. If he prepays $20,000, he may deduct $12,000 in 2020 and the other $8,000 in 2021.

In Backemeyer v. Commissioner, 147 T.C. No. 17 (Dec. 8, 2016), the tax court explored the interplay between prepaid expenses and the step-up in basis. A farmer prepaid input expenses for the following crop year before he passed away. His wife inherited his property, including the seed, fertilizer, and herbicides, with a stepped-up basis. The IRS argued that the wife could not again deduct the cost of those inputs when she used them to plant a crop. The IRS argued that the tax benefit rule would require recapture of the earlier deduction. The Tax Court disagreed, finding that the estate tax effectively “recaptures” IRC § 162 deductions by way of its normal operation, obviating any need to separately apply the tax benefit rule. Even though this farmer’s estate did not owe any estate tax, the fair market value of the inputs was considered for purposes of determining whether such liability existed. Recapturing the deduction could effectively result in a “double taxation” of the value of the farm input.